Wind the clock back nearly 200 years to the 18th century and you enter what is often referred to as the “Golden Age” of watchmaking. It was during this period where the works of some of the most prominent watchmakers to ever roam could be sourced back to, and you will come across names such as John Harrison, Antide Javier, Jean Antoine Lépine and the most famous of them all, Abraham-Louis Breguet. It is from this particular era of watchmaking that François-Paul finds inspiration and more particularly, his pursuit for chronometry. Worth noting that 200 years ago, a proper clock or watch was the only way with which to tell time and without the product of a great watchmaker, well, not much could be done. Watchmakers were at the forefront of the world’s advancements and rightfully so since so much depended on their work. Could one have safely gone to sea were it not for John Harrison’s problem-solving regarding the so-called “longitude problem” and his tremendous research in improving the Marine Chronometer?

François-Paul learned much regarding this era during his first apprenticeship under his uncle, in Paris, during the late 70’s/early 80’s. It was during this apprenticeship that Mr. Journe says he learnt his most valuable lessons in watchmaking i.e. by being a restorer of antique clocks.

Today, with all our advancements, watches no longer serve the same importance but for Mr. Journe, he still works as if watches are the only way in which to tell time. This further feeds into Journe’s true calling which is that of Chronometry. I have always said that alike doctors or scientists, watchmakers also develop specialties. While some watchmakers focus on finishing as a primary objective, as an example, and they excel at it, Mr. Journe has always been obsessed with Chronometry and it is where the basis of his work lies.

The Origin

Considering Journe’s obsession with chronometry, it often begs the question of, “If he were to make a watch for himself, what watch would be his ideal timepiece?”

It was this precise question that Journe was once asked sometime in the late 1980’s by a close friend, and it was perhaps this exact question that lit the spark for the watch that would later be named and referred to simply as Chronométre Optimum or in plain English, The Optimal Chronometer.

Journe’s response to that question was to simply have a three-hand watch, displaying only time, but the movement would utilize twin barrels in parallel, a Remontoir d’Egalité and a special escapement. Together, these three components would work together to best-solve the problem of friction within a precise mechanical watch.

The idea for Journe started in the late 1980’s but he admits he lacked the appropriate experience to work on the timepiece from the start. Throughout the years he kept drawing it and imagining it but it always remained in a drawer as he would be working on other projects. He has however mentioned that it always played around in his thoughts and each time he would start to work on it again, it would be a fresh experience considering he had to update the idea with whatever he learned since his last attempt. Even though this watch only saw light in 2012, it actually inspired the Tourbillon Souverain and even perhaps the Chronometre Souverain which debuted well before the Optimum and by several years.

The goal of this ideal chronometer was simply; precision. To achieve this goal Journe applied a simple formula which in his words was, “All the spices that make a good meal.”

Before jumping into these spices, let’s understand the definition behind precision more concretely. Precision, contrary to popular belief, is not determined by how much time a movement gains or loses within a certain period of time, but rather it is more about “stability” and “consistency”. In watchmaking, a precise movement is one that gains/loses the same amount of time more consistently, for example, gaining the same 5 seconds every day. An imprecise movement will be more unpredictable, gaining 5 seconds one day and losing 6 seconds the next day. So the goal for a precise timepiece is to have a more “stable” rate rather than an unpredictable one with fluctuating rate gains and losses.

That said, what would affect precision? In a watch movement, you have energy loaded within a spring in a barrel (known as the mainspring) and as it unwinds, it releases energy which moves through the movement of the gears, under the regulation of the escapement. The goal to achieve a precise, or more “stable” rate is to make sure that the energy reaching the escapement is consistent. One of the biggest factors contributing to poor energy flow is friction. With friction, the energy flow becomes interrupted and that often leads to poor rates.

Now back to the Chronomètre Optimum, let’s look into how Mr. Journe uses his “spices” to ensure the most consistent flow of energy and to eliminate any friction within the movement.

The first thing that Mr. Journe added was the use of a double barrel system placed in parallel. It is somewhat of an “old recipe” that he used for his Chronometre Souverain, which debuted in 2005. The double barrels in such a setup are not meant to provide a longer power reserve (though the Optimum has 70hrs) but rather meant to provide a more “stable” source of energy. Having two barrels placed in parallel allow for less friction on the main gear (or center wheel) of the movement. The idea is to split the pressure of the source between two barrels rather than plenty of torque from just one, or several in series. To note, the Chronometre Souverain was Journe’s most precise wristwatch in a stationary position due to the double barrel setup, however, in theory, it has been surpassed by the Optimum in 2012. That said, the CS still receives high praise from watchmakers at Montres Journe due to its tested precision and performance throughout the years.

The second thing that Mr. Journe added was the Remontoir d’Egalité, which is a constant force device. To explain the concept of constant force, let’s first picture a pullback toy car. When you pull it, you can feel the winding of the spring inside the car. Now release it. The car jolts forward and as the spring unwinds and loses energy, so comes loss of torque. The result is the car begins to slow down until it eventually stops.

The second thing that Mr. Journe added was the Remontoir d’Egalité, which is a constant force device. To explain the concept of constant force, let’s first picture a pullback toy car. When you pull it, you can feel the winding of the spring inside the car. Now release it. The car jolts forward and as the spring unwinds and loses energy, so comes loss of torque. The result is the car begins to slow down until it eventually stops.

Now in a watch movement, the same concept is applied. When the watch has a full power reserve, the torque from the mainspring is greater and thus the energy going into the escapement is essentially greater, increasing the balance wheel’s amplitude. As the barrel unwinds and the torque drops, the balance wheel’s amplitude drops.

To confront this problem, watchmakers use constant force devices, in this case a remontoir. Journe completed his remontoir in 1983 for a tourbillon pocket watch and first added it into a wristwatch in 1991, the first wristwatch he ever made (also the first time a tourbillon wristwatch featured a remontoir). The Remontoir acts as an intermediate spring that regulates the energy going to the escapement. It ensures that the energy is the same regardless of whether the watch is at a full wind or towards the end of the wind. It does this by loading small amounts of energy and then releasing it in stable increments.

The effect can be seen on the dead seconds display seen on the back of the movement. The dead seconds comes as a natural display and shows the energy “as it hits” the remontoir. Flip the watch around to the dial, and a small seconds hand shows the 3hz display of the energy “after” it hits the Remontoir. While one stops as a dead seconds the other is consistent and ticks smoothly at 6 beats per second.

What is interesting about the Optimum’s remontoir spring is that it is made from titanium, for the first time ever. The decision came as a result of titanium being much, much, lighter than steel, which is used in Journe’s tourbillon models. The problem with steel’s heft is that it can somewhat affect performance with the movement of the wrist. The lightness of titanium reduces that effect since the weight is miniaturized and wrist effects would be ultimately be reduced.

The third problem that Mr. Journe had to face is actually one that dates back for centuries; and that is the lubricants and their volatility. The problem with lubricants is that over time, they begin to break down, which leads to added friction within the movement, and a loss in the watch’s performance. Whereas today, we have much better synthetic oils compared to the 18th century when oils were made from animal grease; the problem has not been eliminated but only improved. Now the oils last longer and are more immune to temperature changes, but still breakdown after 4 or 5 years. This is typically why the usual time to send a watch for service is every four or five years, as that is how long the oils generally last. Hence the issue is not in the use of the oils themselves, but rather in their natural volatility.

To note, different friction points within a watch use different lubrications. For example, a barrel is a watch part that sees relatively little movement and often has large pivot points and thus the lubrication used in the area is quite dense and not volatile. As a result, the lubrication can last a longer time without breaking down and this generally serves little concern to watchmakers, for now. As you trace a gear train towards the escapement, which is fast paced and brutal considering the speed at which the pallets slide, and the balance wheel oscillating back and forth; watchmakers use lighter and more volatile lubricants. The lighter lubricants are used here since denser ones would obviously require more energy and would probably stick but, on the downside, lighter lubricants breakdown much quicker.

The solution is to this was to eliminate any lubricants and for Mr. Journe, he was faced with two options. The first option, popular in today’s industry, is the use of solid lubricants; otherwise known as silicium or silicon. Silicium eliminates the need for any lubrication but it is like glass and therefore extremely fragile. The problem with using silicium, is firstly, the watch itself becomes prone to damage from day-to-day use. Mr. Journe believes a watch should be able to withstand a good knock while on the wrist and would sometimes literally slap a watch against his thigh or palm without any worry, certain of a watch’s durability. The second problem with silicium is it requires high tech machinery to produce them and further, the parts cannot be repaired. Silicium components need to be completely replaced and if one does not have the means to do so, the movement cannot be fixed.

François-Paul has tested the use of silicium in the past and praised its performance but has rejected its use saying, “My watchmaking philosophy is to make watches that will still work in 200 years.” Further, he finds it incredible how watches made nearly 200 years ago can work flawlessly today, and he hopes to keep uphold this notion. To him, silicium is, “the wrong solution to the right question.”

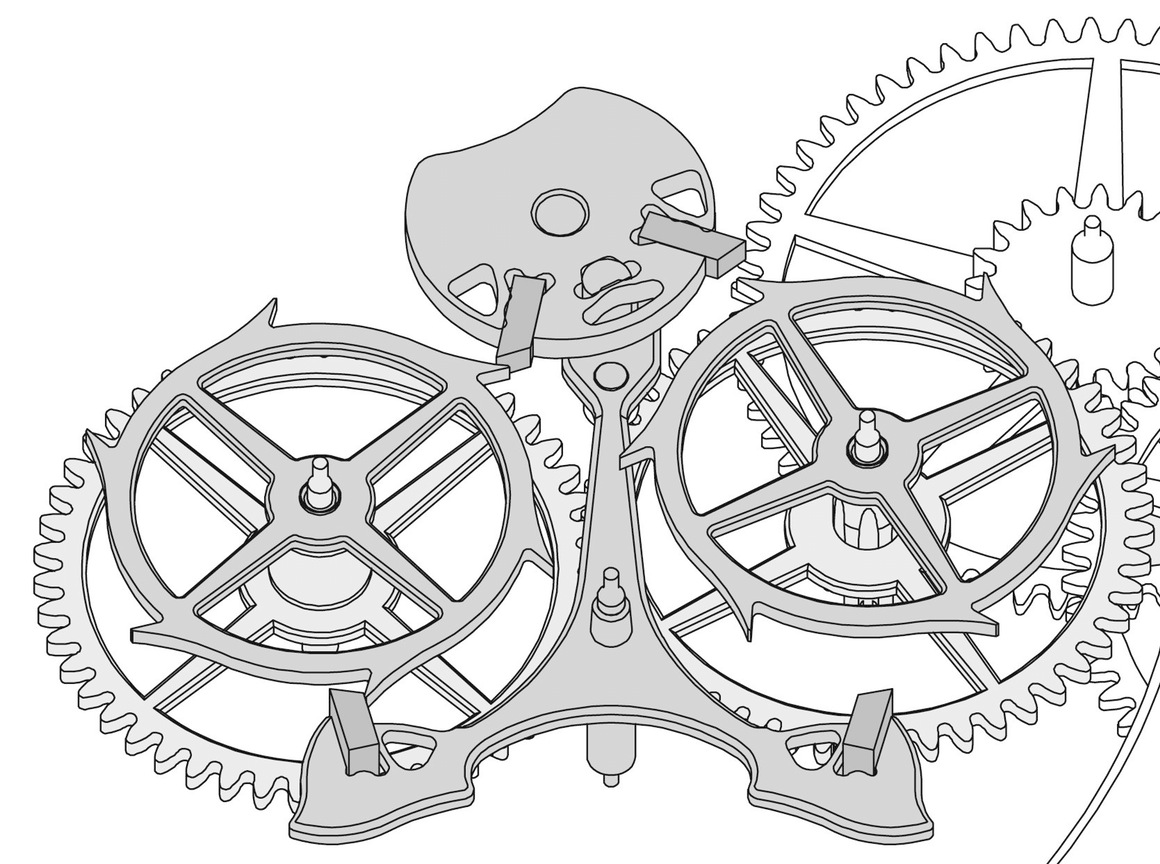

Since silicium cannot be used, Journe decided to go the other way using a far more traditional approach; that is by using two escapement wheels. Having two escapement wheels allows you to divide the pressure by two, which at the small level of a movement makes a huge difference. By doing so, one does not need any lubrication since the escape wheels are merely only being caressed rather than rubbing against the pallet jewel, which would otherwise require lubrication which would interrupt the energy flow.

There still remains an issue with the designs of dual-wheel escapements which is that they are not self-starting and require a “kick” to start. The only way about this so-called flaw was to design his own escapement which mixed the most efficient dual-wheel, Breguet’s “natural” escapement, with the swiss-lever escapement which was self-starting. The result is a patented high-performance bi-axial direct impulse escapement (EBHP), which is the only one of its kind to start on its own; as soon as the energy reaches it. Next time you spot an Optimum not ticking, wind it one turn and you will notice that it probably starts ticking quicker than a watch using a swiss-lever escapement.

A significant advantage to eliminating lubricants within the escapement is that now the watchmaker cans et the watch much more precisely from the start without having to take into account a break-in period or the fact that the lubricants might alter performance in six or more months.

The final spice that Mr. Journe added to the movement lies with the balance wheel/spring itself. The Optimum is the only Journe in today’s collection that utilizes a Phillips curve with regards to the hairspring, allowing a more concentric movement thanks to its three dimensional shape.

To put it all into perspective, the Optimum began as an idea in the 1980’s and began taking shape on paper by 2001. The escapement however, only saw a completed sketch by 2007. All-in-all, the Optimum went through several redesigns and Journe noted that it underwent significant delays due to the many redesigns it went through to ensure a consistent flow of energy, as it should have.

The Design

The result of such a long pursuit is a beautifully simple time-only display, adopting a slightly larger signature off-centered Journe display on the dial side accompanied by a 70 hour power reserve indicator which contrary to other PR indicators, does not display howmuch power remains within the two barrels but rather, it displays how long it has been since the watch was last wound. To clarify, at a full wind it will display “0” hours, and when it displays 40 hours, it is actually relaying that it has been 40 hours since you last wound the watch. The idea is one that Journe uses for all his manual-winding watches and is reminiscent of early French Marine Chronometers. Lastly, as an added touch, Journe has incorporated a peep-hole just above the seconds hand; which displays the remontoir’s air brake mechanism that jolts every second, a constant reminder to what lies within the watch itself.

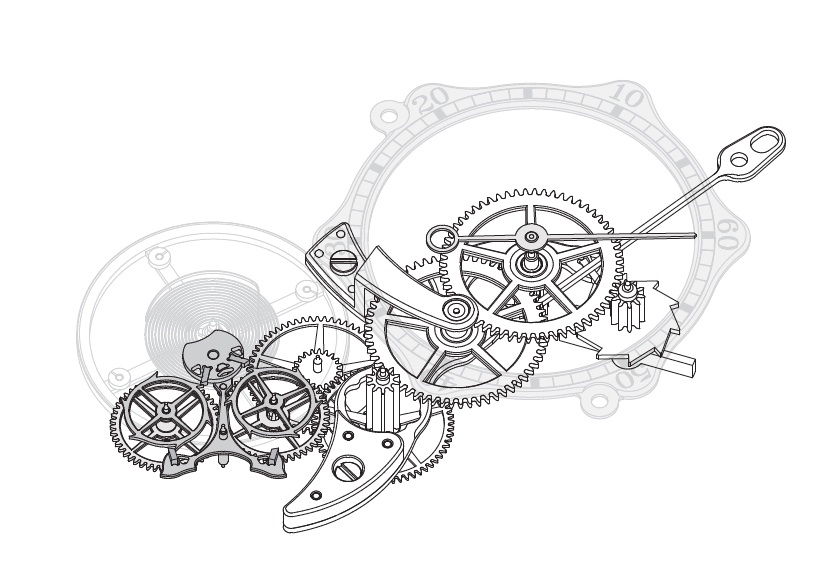

Flip over the watch and prepare to be thrilled by how complex yet visible all the spices are within the movement. To the left of the rather symmetrical movement, Journe has placed two, rather large, barrels and an attractive 18k rose gold bridge covering them. To the right, a more open and in-depth display of the gear train. First, the rather intriguing “natural” dead second ring which, if you look closely, goes counter-clockwise. The interesting thing about this dead second ring is that it was not intentional. As explained earlier, it comes naturally from the remontoir and Journe figured that purely for fun, since there was a pivot, he would put a hand on it turning it into a dead second.

Now why does the hand go backwards? The answer is quite simple really. The display is natural, and for Journe to reverse it, it would mean adding unnecessary parts and gears which would lead to more friction points and more complicated servicing, which contradicts the goal of this watch; which is to reduce friction and to have a highly efficient energy flow.

Just south of the dead seconds counter lies a very attractive balance wheel, which at 10.1mm diameter is a Journe standard. The large balance wheel combined witht he phillips hairspring results in a better equilibrium as mentioned above. The balance wheel is further is mounted just above the more hidden EBHP escapement. Although the escapement remains mostly invisible, it does produce a highly audible ticking which for the owner, is perhaps the greatest escapement music to the ears.

So now with the Chronometre Optimum, what exactly does one look for? Again, the goal is to ensure a constant amplitude for a long period of time, since that is what precision is based upon; a stable reading. Upon testing the movement, Mr. Journe found that the watch maintained its amplitude for 50 of its 70 hours of power! A spectacular achievement and sign of the watch’s success.

What’s Next?

Today, the Chronometre Optimum has been crowned as F.P. Journe’s most precise timepiece and although being a time-only watch; it’s certainly one of the most complicated watches he ever made. The master watchmaker does not deny that the Chronometre Optimum is a great leap in terms of making a great chronometer but he will not call it ‘The Holy Grail’. To him, there is still much to do in order to find the ultimate chronometer but the Chronometre Optimum serves as a goal and symbol towards the greater objective, which will most likely not be achieved in our lifetime.

2 responses to “In Pursuit of Precision: Breaking Down the Chronométre Optimum”

I sold five incredible watches to afford my 40mm platinum Optimum. This article goes into the detail necessary to appreciate the genius of both F. P. Journe and the Optimum. Sometimes I feel remorse for what I had to give up but in the end, owning this amazing watch and appreciating it is worth it.

Awesome article!