It is fair to say that alongside the Tourbillon Souverain, the Chronomètre à Résonance is one of the most cherished F.P. Journe timepieces within the world of Journe collectors. First introduced at Baselworld in 2000, it has gone through an array of changes over the years but still remains one of the most unique creations to ever result from the creative mind of François-Paul Journe.

To note, whereas F.P. Journe’s Resonance stands as one of the more controversial Journe watches, I will not get into the details of the two arguments, i.e. does it work the way Mr. Journe claims it does. However, if you are interested in reading more into that research, I highly urge you to take a look at this article here, written by fellow watch blogger, Mr. Jack Forster.

In brief, the Resonance is a remarkable timepiece that basically uses two completely separate movements with the balance wheels placed very, very close to each other (around 0.4mm apart). The close proximity allows them to pick up each other’s vibrations and eventually sync to the same exact beat. Essentially, the whole goal is to use the resonance phenomenon in order to counter the wrist movements that would affect the watch’s accuracy. You see, if one balance wheel falls out of step, the other will slowly bring it back to sync.

The following is lifted from F.P. Journe’s website and will hopefully give you a clearer understanding:

“Every oscillating object sends out vibrations. Nearby bodies absorb the same frequency. It’s the principle used to tune a radio to the right station.

In the case of the resonance wristwatch created by François-Paul Journe, each balance alternately serves as exciter and resonator. When both balances are in motion, they reach a state of “sympathy” throught the effect of resonance and began to beat naturally in the opposite direction. The two balances therefore support each other, giving greater inertia to their movement. This harmony is only possible if the difference in frequency between the two is no more than five seconds per day accumulated in 6 positions. Adjusting them is an extremely delicate task. While an external disturbing movement affects the running of a traditional mechanical watch, in the case of a resonance watch this same disturbance has the effect of accelerating one of the balances and slowing down the other. Little by little, the two balances come back together to reach a point of agreement and thereby eliminate the disturbance. This innovative chronometer offers a level of precision that is unrivalled among mechanical watches.”

Yes, quite remarkable indeed! That said, since Mr. Journe is so inspired by watchmakers of the past, let us start our journey all the way back to…

Resonance in the History of Horology

The first written document regarding Resonance can be found in the works of Christiaan Huygens, a Dutch scientist who invented the pendulum clock back in 1656. He found that placing two clocks within close proximity resulted in them influencing one another. Since Huygens was not a clockmaker, more a scientist, he ended up contracting his designs to a clockmaker by the name of Salomon Coster, in The Hague. Unfortunately, no actual clocks have been found from that time but what we do have are the earliest written documents regarding the invention of pendulum clocks and the first occurrence of resonance in horology.

Fast forward nearly 100 years later (18th century) and we find the second occurrence of resonance and this one perhaps being the most prominent. The French clockmaker Antide Janvier, royal clockmaker to France’s Louis XVI, made three resonance regulators in his lifetime, or at least that is what we know of so far. One of these regulators is kept at The Musée Paul-Dupuy in Toulouse, France; another is located within The Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, which is the smallest of the three; and the last and according to Mr. Journe “most interesting” is proudly the property of Montres Journe in Geneva. It was purchased by Mr. Journe at a 2001 auction for just north of $1.4M at a moment he described as “extremely emotional”. It currently lies within the company’s conference room alongside Journe’s watchmaking awards.

Like the most famous watchmaker in history, Abraham-Louis Breguet, Janvier was also a genius in horological history but went through a more complicated life; having bankrupted all his businesses, he eventually ended up selling his workshops to Breguet sometime in the 18th century.

According to Mr. Journe, Janvier probably ended up working for Breguet as Breguet ended up producing two resonance clocks shortly after. One of the clocks was made for the King of England, King George IV, and still remains in Buckingham Palace (Breguet No. 3671); the second was made for Louis XVIII (Breguet No. 3177) and is currently kept at the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.

It was likely due to Breguet’s encounter with Janvier that he decided to experiment further and apply the resonance phenomenon into pocketwatches, which he succeeded in doing. Those pocketwatches were delivered, again, to the King of England and Louis XVIII. The watches later ended up under the care of renowned Breguet collector Sir David Salomons whose collection was later donated by his daughter to The L.A. Mayer Institute for Islamic Art, in Jerusalem, where they rest today (the collection also includes Breguet’s ultimate work, The Marie Antoinette).

Such was the case, two pocketwatches ever made, until in 2012 when a third was found and appeared at an auction; the watch that nobody knew existed. It was purchased by the Swatch Group for the Breguet Collection for a sum of over $4.5M.

Photo credit: Hodinkee

And that as Mr. Journe said “…is the end of the story of Resonance…”

François-Paul Journe Meets Resonance

François-Paul’s first job was working as an apprentice under the guidance of his uncle, Michel Journe. His uncle owned one of only a very small handful of antique restoration workshops in Europe back in the late 70’s/early 80’s. Fortunately for a young Mr. Journe, who was only in his early 20’s, that meant access to some of the most important clocks and watches made in the history of horology. In fact, it was through this experience that François-Paul inherited much of what he knows today and continues to pass down one of the strongest words of advice he ever received;

“If you want to be a great watchmaker, you need to visit museums. If you don’t understand what you see, you need to visit the library and read. If you don’t understand what you read, you need to go back to the museum and see. It is only through history that you can become great in the future…”

During his apprenticeship, François-Paul was contracted to restore some clocks for the Musée des Arts et Métiers and it was then that he first encountered the resonance phenomenon. François-Paul came across one of the two resonance regulators that were manufactured by Breguet, specifically No. 3177 which was delivered to Louis XVIII in 1819 or 1821. This clock would become the most mysterious and poetic clock he would ever handle in his restoration career.

Photo via John Kirk’s Compilation

He recalls having to really study a lot about how the clock worked since the last time anyone really spoke about resonance was nearly 200 years ago. It was something of a legendary tale to him, one could say. It didn’t take him a long time to figure out how fantastic the system was and upon offering his first client a watch (after Journe’s very first pocketwatch in ’82), it came as no surprise that François-Paul offered to fabricate a resonance pocketwatch.

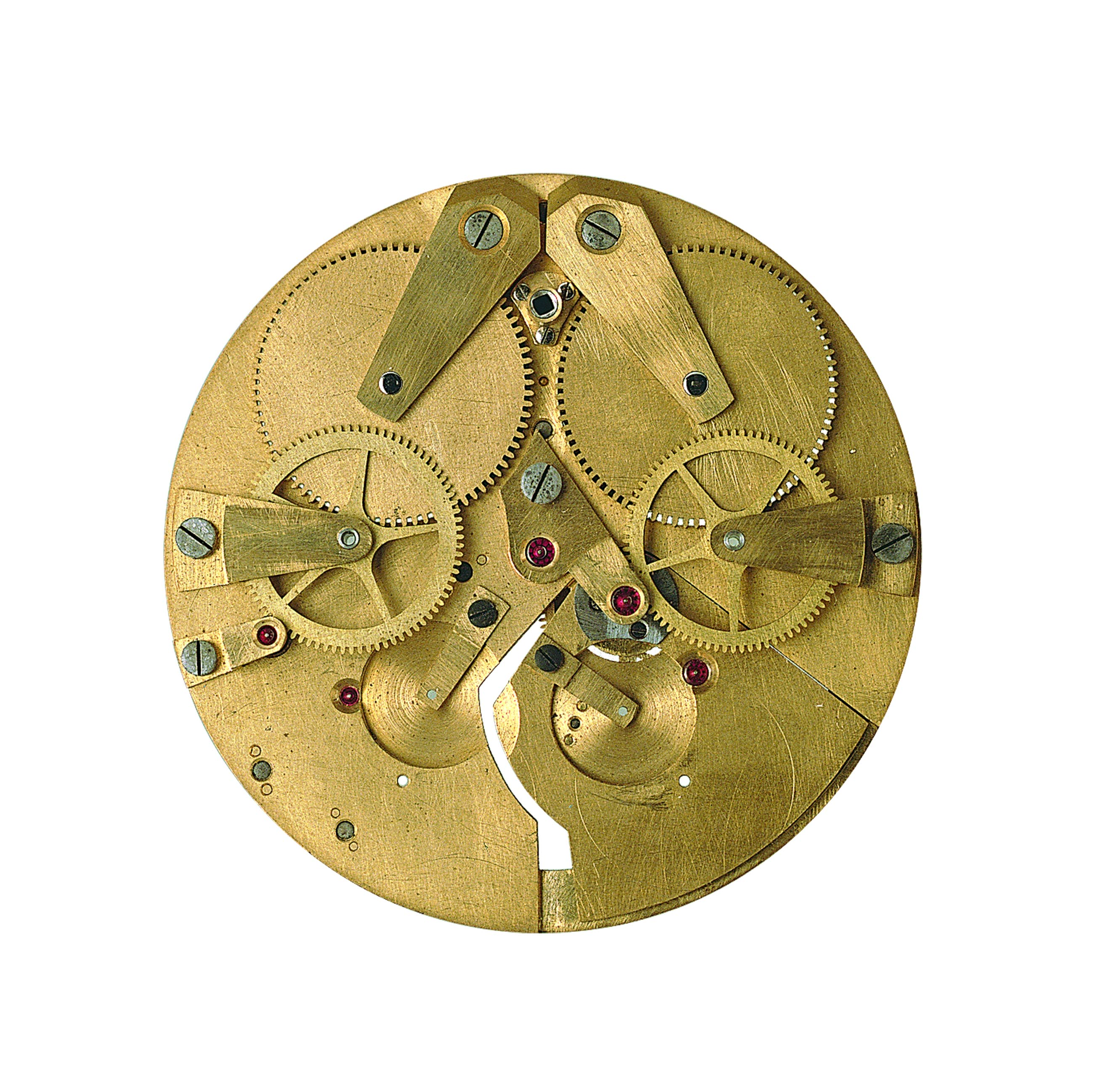

He worked on the watch for two years before finally delivering the watch to its owner in 1984. However, keep in mind that this was the first watch Journe made for a client and the second watch that he made, ever. Consequently, his lack of experience meant the client returned the watch as it did not work as expected. It is worth mentioning that the client walked away with Journe’s 3rd watch shortly after, which happened to be a completely new tourbillon pocketwatch with a remontoir d’egalite. On the other hand, Journe dismantled the resonance pocketwatch and all that remains of it today is an uncased movement, property of The Montres Journe Museum.

“After my attempt in making my first commissioned pocketwatch, it wasn’t my best experience so I forgot about the resonance principle and continued making other watches for customers. However, I don’t like to lose so I told myself one day, one day I will win at this. I’m ok with losing the battle but not the war,” François-Paul mentioned.

It wasn’t until 1994 when Mr. Journe saw another fellow watchmaker, Mr. Philippe Dufour, release his Duality that he decided to reattempt making a resonance watch. To note, the Duality does feature two balance wheels for better precision but does not make use of the resonance phenomenon.

Photo via SJX Watches

Thus, he began drawing it and designing it, this time applying the principle for the first time ever into a wristwatch, something never done before and one could argue never done (in a natural way) by anyone else to this day.

The design of Journe’s Resonance came slower than he had hoped as he was also working on other developments including his Souscription Tourbillon series (yes, back in 1994 along with designing the starting collection of his future brand).

Back when he made his first prototype, Journe was still subcontracting watch components so some plates, bridges, etc. were manufactured for him and upon assembling his first prototype, he had a bit of a concern. He found that the energy flow in a wristwatch was much, much less than that in a clock or a pocketwatch and expressed his worry saying, “I had no idea if I would be successful or not.”

His worry did not stop him and François-Paul kept pushing himself hoping that someday, he could finally get it done. At one point, he showed the watch to a friend of his who told him to keep going and even though it might not work, it is so beautiful that he will definitely find good use for it someday. It is fair to say that die-hard Journe fans owe this friend quite a lot for those words of advice.

Something Mr. Journe would frequently do with his prototype was carry it in a plastic case, in his vest’s pocket, while walking through the streets of Paris. Every now and then, he would put the case to his ear and listen to see if the movement was resonating or not. In fact, this is something he still does to this day and if you haven’t tried it, it is quite fascinating listing to two balance wheels beat as one.

At first, the resonance effect was almost non-existent but after some months of regulation, it finally worked and this master watchmaker succeeded in making, for the first time ever, a wristwatch that uses the natural phenomenon of resonance.

It was only after that moment that Journe cased up the movement in a proper case with a dial and hands, however, despite the planned launch in 1998, it got delayed as he was still finishing up some Souscription Tourbillons.

And that ends this portion of the story…